- Home

- Ann Howard

Carefree War

Carefree War Read online

Copyright © Ann Howard

First published 2015

Copyright remains the property of the authors and apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission.

All inquiries should be made to the publishers.

Big Sky Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 303, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia

Phone:

1300 364 611

Fax:

(61 2) 9918 2396

Email:

[email protected]

Web:

www.bigskypublishing.com.au

Cover design and typesetting: Think Productions

Printed in China by Asia Pacific Offset Ltd

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry (pbk.)

Author:

Ann Howard

Title:

A Carefree War

ISBN:

978-1-925275-19-3 (paperback)

Subjects:

Australian History, Child Evacuees, WWII

Dewey Number: See National Library for CIP data

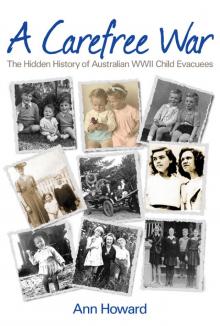

Front cover images:

‘Rabbit Boys’ - Andrew Kyle (right) and brothers.

Cassie and Jim Thornley in a hand tinted photograph.

Warren and Peter Daley, Cessnock.

John, Marie and their mother Eileen, Glen Innes.

Evacuees Geoff Northcott and Ian Newton with Alan Wilkinson and neighbours on a rubber drive to help the war effort.

HMAS Kuttabul sinking in Sydney Harbour.

Bruce H Crawford aged about 18 months.

Queenie Ashton evacuated two of her children to Armidale

RDB Whalley with his three sisters, Armidale.

Back Cover:

Young Kevin Murphy races past Lion Island

Images and photographs are either out of copyright and in the public domain, paid for to the owners or reprinted with kind permission of the contributors.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

I was a Rabbit Boy

Cherry Blossom Land

Who’s Telling the Truth?

Call to Action

What is Really Happening?

Getting the Children Away

Will We Lose Our Country?

Keep Calm and Carry On

Empty Desks

Handkerchiefs and No Pets - The Evacuation of Torres Strait Islands, Northern Territory and Queensland

Staying with Friends

Mum Slept Through the ‘All Clear’

Going to Grandmas

No More Flowers - Western Australia

Tasmanian Fears

I Want to Go

Changing Lives

G’day! Being a Host

Victorian Evacuees

Aftermath

Contributors

About the Author

Index

Acknowledgements

The wave of voluntary evacuation of children around Australia from 1939/1945 is hidden history, despite long-standing public interest in WWII. To unearth it, I needed the warmth and generosity of the many contributors Australia wide, who gave me photos, newspaper cuttings and reminiscences, and I am very grateful. They are listed in the book.

When I gave public talks, the audience enriched me with ideas. Everyone was so encouraging, I was further inspired. I’d like to give a special mention to Andrew Kyle for his original story which planted the seed of the book in my mind, and my partner, Robert Bickerstaff for patient listening, editing and great advice as always. My boys continue as my best fans. Sadly Lincoln, my middle son passed away in March 2015, at aged only 46 and I will so miss his enthusiasm and intelligence. My good doctor, Helen Greer kept me alive and kicking. Among the many well versed archivists and historians who supported my research are Lindsay Read - Children’s Services, Kate Riseley - Archivist at Shore School, Judy Grieve and the historians at Armidale. Associate Professor Bev Kingston, my respected mentor from university days encouraged me. Geoff Pritchard gave invaluable technical advice. The Vincent Fairfax Family Foundation for Trove is a boon to armchair researchers, without charge. And I can’t forget Roma, ageing dog companion - her approving gaze is on me as I write!

When I came to Australia, and was naturalised in the 1970s, I was immediately drawn to her history. My books about women, drovers, the AWAS, child migrants and other hidden histories sold well and I was able to do more research. Everyone has a story and I love to tell it.

Although aware of the tremendous sacrifice of the Australian men and women in WWII, I believed the Australian home front relatively safe. It was only after Andrew’s chance remark, Christmas 2013 that my eyes were opened to voluntary child evacuation. Australia’s story of WWII is not complete without their stories.

Foreword

British TV has the so-called Hitler Channel for stark scene-setting from WWII. Less organised but still poignant in many ageing Australian minds are images of the Japanese invasion that very nearly happened.

1942 rises as the Year of the Panic, with stub-winged warplanes over tropical islands and Sydney people hastily selling their harbourside homes. I recall my father, that winter, setting off with military rifle and overcoat to look for fifth columnists said to be signalling out to sea by night, and his frightened determination to defend our farm against trained enemy soldiers.

1942 is the sudden start of unaccompanied train trips by children being sent inland to rural relations. Frightened mothers, whose menfolk were fighting in the islands made far-reaching decisions as to where the family, sometimes barely out of babyhood, might find refuge.

Ann Howard, herself a child evacuee from European hostilities, records the shifts and displacements of a time when governments did little for the civilian population except lie to it through censored media. She details the largest upheaval since white settlement from oral memoirs and box camera photos, all placed within frameworks of history

Les Murray

Introduction

Fear of losing your country, the red dirt beneath your feet, is a very real, breathless fear. Australian women, whose men had gone overseas to fight in WWII, paused at the sink and watched their children laughing at play in the back yard. It was unthinkable that Australia could be invaded. Yet after Pearl Harbour, then the fall of Singapore to the Japanese on 15 February, 1942, it was a sickening possibility. As they brushed their children’s hair in the evening, they wondered what was going to become of them. The Rape of Nanking in the old Chinese capital, by the Japanese in 1938 had left them in no doubt what would happen to civilians in the path of that Army.

The Japanese Imperial Army moved swiftly up the Malay Peninsula, ‘take all, kill all’, with a crab claw threat towards the island of Australia. The conflict that had echoed in distant Britain was now on their doorstep. Scanning smudgy, censured newsprint to try and find out what was happening, women on the home front in Australia whispered to their mothers and sisters that they thought the Japanese Imperial Army was going to invade. But where? Geraldton, Western Australia? Port Kembla? Sydney Harbour? Newcastle? Armidale? Hobart? Or up at the top of Australia? Yes! That’s where it would happen.

Troops had been sent up to the Atherton Tablelands and the Queensland Government had evacuated civilians. They would probably relinquish the top of Australia to the Japanese, was their reasoning. It was mythical, but it was called the Brisbane Line. It was happening - sisters and girlfriends had donned Service uniforms and some were secretive about their postings. Japanese lightning raids were not reported in the Press, so civilians became cynical about official information. Wherever they

thought the Japanese might land on the coast, or pick a target, they wanted to get their children away safely away to the mountains and inland.

Like animals that drag their young to a safe place away from predators, they did not wait for official sanction; they fled, in their thousands. The beach became a dangerous barbed-wired place, the Sydney Harbour a netted area. Irrational decisions were made; children were evacuated to Lithgow, where the Small Arms Factory was, and Lithgow children in turn where evacuated away.

As children were hastily dressed and bundled into trucks and cars, they had no idea of the grim reality of the situation. They thought they were going on holiday. They would have a carefree war.

Chapter 1

I was a Rabbit Boy.

Little Andrew, wandering the Oberon farm, found a rusty motorbike on its side in a back paddock. He stood staring at it for a while, thinking …

If only I could find a couple of wheels, I’d be out of here!

In Australia, families clustered round the wireless heard Robert Menzies’ announcement on the evening of 3 September, 1939: ‘Fellow Australians! It is my melancholy duty to inform you that in consequence of the persistence of Germany in the invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war on her and that as a result, Australia is also at war’.

Meryl Hanford remembers her relative’s plans:

The government seemed unconcerned in the 40s and it was left to people to make private arrangements about their children.

Andrew Kyle remembers his evacuation experience as a ‘rabbit boy’:

Due to the Japanese scare, I was sent to Oberon from 1940-41 with my brothers. When we came back home, people didn’t question where myself and my elder brother had been for nine months. My parents knew these people and we’d been invited to stay in their old shack on about 100 acres. We went up there in an old ‘Whippet’, loaded up to the roof. When the old man saw the state of the place, he cooked up a story about an urgent recall to the city (for him).

The iron roof was lined with chaff bags with creatures running along inside. There were no doors, just bits of hessian hanging down. It was six miles out of town along Shooters Hill Road. If you wanted to move anything, there were some old wooden sleds and moth-eaten nags you had to catch and harness up to do so. Peas were the cash crop. A couple of hard-bitten daughters sat in rocking chairs on the veranda taking pot shots at the birds. There was a wind up gramophone, with one record for entertainment. My younger brother was about two years old and still in nappies - we had to change him when we couldn’t stand it anymore - my older brother usually did that!

The lady of the house was a short order cook in the town and she left in the sulky before dawn. For breakfast we’d have a bit of bread to toast smeared with butter or dripping. We had no electricity so we would need to get the fire going first and our toaster was a fork made from a bit of fencing wire. There was a Coolgardie safe and a chip heater. Water was always scarce. Ma, the old lady, put our little brother in the corner of her room on a palliasse. He woke up to hear a tinkling noise and it was Ma on the ‘po’.

‘What are you staring at?!’ she would yell.

He hid under his blanket. We were rabbit boys.

The old bloke was a bush carpenter and went away putting up sheds for people. He only had one eye, but he knew where the traps made from loops of fencing wire were. He had a very sharp knife. There were lots of snakes as we walked the property and we were warned to keep away. We boys were from the city and stood aghast as he grabbed a screaming rabbit and cut its head off. He’d ring the paws and deglove the rabbit of its skin. These were sold to make Akubra hats. They had a few mangy dogs, which were thrown the carcases. Every night we had rabbit for dinner, every way you could think of - roast, stewed, fried.

The strainers on the water tanks had long rusted away. They tipped the tanks on their sides and we were small enough to crawl through the holes and scoop out the sediment. There were remains of reptiles, birds and small mammals in the mud. The family said the water never tasted the same after the tank was cleaned out! It was a bit difficult to have a bath as water was always at a premium. As it got near Christmas, the old man went out and grabbed one of the mangy looking chooks and cut its head off. It was running around with blood spurting for what seemed like forever. Another thing I’ve never fancied eating! One time, they fattened a pig up, killed it and put it in a bath of salt. They didn’t really know what they were doing. You couldn’t eat the meat so they buried it in the end.

They had a dog that was tied up on about six foot of chain because it had savaged a sheep years ago. It was tied up for punishment then just left in the sun and snow. You couldn’t go near it, poor thing. A cow wandered into the quicksand and my brother had to run the six miles into Oberon for help. By the time people came with ropes, the poor cow had disappeared. There was an old motorbike, rusty, with both wheels missing in one of the paddocks. I used to stare at it and think, ‘If I could find two wheels, I’d be out of here’. Two Italians, classed as enemy aliens, Vincento and Arnaldo, were sent to the farm for two days here and there. We looked forward to them coming as they were really nice guys. Sometimes a pile of comics would arrive that had been sent by relatives and that was bliss.

Andrew had fun on the Oberon farm, as children usually do. Many child evacuees had a blissful time in the country, being spoilt by grandmas, aunts, uncles, cousins and friends, able to disappear into the paddocks, dropping into bed exhausted to sleep soundly.

The Australian Women’s Weekly, December 27, 1941 reported, ‘In every coastal city in Australia this last fortnight, one question has run like a refrain through the news and rumours of war. It is: What are we going to do about the children? Ever since Europe felt the full horror of aerial warfare, the plight of children has aroused the indignation of men and women. Now, when Australia is in imminent danger, hundreds and thousands of parents are thinking mainly of one problem - the safety of their youngsters’.

Councils had interminable meetings and mostly decided that there was no future in voluntary evacuation, that it must be funded and compulsory. But how would they enforce it?

Col (Colin) Gammidge was a child evacuee who left Merrylands to go up-line to his small country town birthplace.

Dad was an NES warden in Excelsior Street, Merrylands, and we had an air raid trench in the backyard. The school (Granville Primary) had concrete shelters in the playground and windows taped with brown sticky tape. I got to see the Japanese submarine after it was recovered from the Harbour and we also went alongside the Queen Mary which was a troopship at the time. I can also remember going through the submarine net to get to Manly in the ferry and how scary it felt to be on the wrong side of the net! We had lots of blackouts and the NES wardens would check that lights didn’t show in the street. There were few cars.

In 1942 my mother took my elder brother Ray and I back to the tiny town, Barmedman, where I was born in 1936. In Barmedman I went to the one-teacher school. I think we stayed in Barmedman for three months or so. Mum’s family came from the area and Dad was an ‘import’ being a railway bloke from Newcastle. I remember when Mum came back to take Ray and me home to Sydney, all I wanted was a ‘milkman’s book’ which is apparently a small black notebook for keeping accounts.

Barmedman lies north of Temora between Wyalong and Temora. Our relation, Merv Hill, had a farm outside Barmedman called ‘Sunnyside’ and a house in town.

The farm ‘Sunnyside’ is just south of the town heading towards Reefton. There were amazing place names like ‘Stockinbingal’ and ‘Gidginbung’ - Dad knew them all in exact sequence being a ‘railie’ bloke of long standing. One day we hit a sheep along the line south of Sunnyside and my grandfather, Albert York, went back the next day, gave it a kick in the ribs whereupon it stood up and trotted off. We wondered if it would have lain there until death or figured out that it was still alive. Albert York ran the railway pumping station at Wyalong (Central), pumping water from a dam into those large overhead water t

anks that dotted the country rail system to replenish the tenders of steam engines

At school we were told about sabre toothed tigers and I remember being terrified there was one in the dark end of the house veranda in De Boos Street, Barmedman. Wheat was the main export from the town and I remember horse-drawn wagons and trucks loaded with bagged wheat at the silo. The trip to Barmedman was a real trek in those days. The Southern Mail (I think?) took you to Cootamundra then you changed to the two car rail motor which was not air-conditioned, a hot trip after the mail train.

Eileen Pye left Sydney for Naradhan, late January, 1942:

Naradhan was the end of the line going west. My husband’s young sister was sent from Sydney to stay with her relatives near Mudgee at the same time. The train left Central (Sydney) at 8 pm and we arrived at Naradhan at 4 o’clock Friday afternoon. By that time we were the only passengers in the only carriage, two thirteen year old girls and an eleven year old boy. The train had disconnected carriages along the way. The reverse happened on the way back to Sydney. I left in September 1943, a 14 year old girl. My cousins stayed until end of school year. I was the only passenger when the train left Naradhan, travelling overnight and arriving at Central about 8 pm. I think my ‘Uncle’ would have tipped the guard to keep an eye on me. By the time the train arrived in Sydney it had reattached carriages at different stations and it was overcrowded with soldiers sitting in the corridors.

In the UK, many city evacuees had never seen a cow or breathed fresh air, and were frightened when they saw the sea. Australian children who were evacuated could run free, play with animals and bring home butter, fresh eggs, and fruit in season, jams and flowers. For some this would be one of the most memorable times of their lives - for all the right reasons!

Cecily Atton:

My sister and I were sent by our parents from Sydney to our aunts and uncles in Narrabri in 1942. We were around fourteen. The food was wonderful - everything was fresh. When school was over, we were out and around on the farm – but had to be careful of snakes. The hens were free range and made nests all over and you had to be careful in case the snake had got there first when you collected eggs!

Carefree War

Carefree War